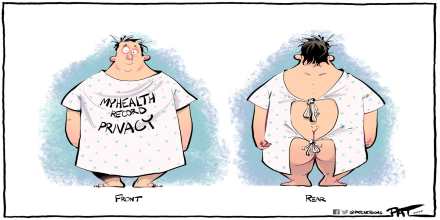

Hovering over the opt-out button on “My Health Record”

October 11th, 2018 | Published in Favorites, Health & Mental Health

I’m that text book case with complex, chronic illnesses for whom the electronic My Health Record (MHR) is supposedly a lifesaver.

I’m that text book case with complex, chronic illnesses for whom the electronic My Health Record (MHR) is supposedly a lifesaver.

I am, however, strongly inclined to opt out, on political (if not personal) grounds.

With a click of a key, so the story goes, up pops the summary of my medical history, medications, immunisations, allergies, test results, x-rays, procedures, medical practitioners’ details, and Advance Care Plan.

All the information needed in an emergency.

MHR will ensure the best care, without adverse events (like oversight of essential medication) and without unnecessary duplication of tests. It will provide a seamless interface, overcoming the incompatibilities of existing systems used by general practitioners, pharmacists, laboratories, and hospitals.

Sounds amazing.

Maybe. But I have doubts and questions.

I think the “life-saving” script is spin. It gets repeated like a mantra without evidence until it assumes the status of ‘Truth’. The more earnestly the politicians spruik the system, the more curious I become about what they are not saying. I resent the sales pitch, feel driven to dig below the surface, and want to invite other people to do likewise.

Hence this post, and the points I expand:

- As with any electronic system, the value of MHR is limited by human factors and the quality of data uploaded to it. In these ways, it’s similar to systems in current use in medical practices. A centralised system like MHR does not guarantee flawless data or faultless practitioners, and its “life-saving” credentials have, I believe, been overstated.

- The multiple agendas of the database need scrutiny. They include commercial, research, and political ends, as well as patient care. I do not believe patient care has high priority in the terms of our neoliberal government.

- Multiple agendas and system insecurity compromise privacy, despite reassurances about safeguards. Privacy breaches are particularly high-risk for several groups including employees, adolescents and those with mental health issues.

- I also have niggling suspicions about mass health data enabling mass government surveillance.

My number one critic tells me this post should come with a TLDR alert (too long; didn’t read at 4987 words). I do hope people persist, think about the issues, consider options, and leave comments at the end.

(NOTE: The opt-out period ends on November 15, 2018. Anyone who has not opted out by that date will have a MHR automatically created for them. You can opt out here.)

The value of MHR depends on data quality

The value of electronic records depends, to state the obvious, on the quality of their data. MHR data thus needs to be clinically reliable and readily accessible. Medical practitioners need to be digitally competent and have time available to search the system.

MHR data thus needs to be clinically reliable and readily accessible. Medical practitioners need to be digitally competent and have time available to search the system.

Clinical reliability

Some information will be uploaded to MHR automatically. This includes GP appointments and other services covered by the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), medications subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), and information on the Australian Immunisation Register and the Australian Organ Donor Register.

Non-subsidised medications may (or may not) be uploaded by prescribing practitioners, who may (or may not) also upload clinical notes and material such as specialists’ reports.

MHR is thus likely to be an incomplete record, and clinically unreliable on that basis. In an emergency, doctors would not, for example, be able to rely on MHR to know whether a patient is taking non-subsidised medications.

Additionally, patients themselves can use privacy settings to limit what is uploaded to their MHR and who has access to it.

User-friendliness of the database

The usefulness of MHR data also depends on how easily it can be accessed. Over the journey, I’ve become aware of problems that already arise in existing systems. For example, at the general practice I attend, you can make an appointment with your regular GP, or see whoever is on walk-in roster. Here are some of my experiences:

- Doctors have not always been able to find my record on the system, even though I’ve been a patient of the clinic for years.

- They have sometimes been unable to find results for tests and procedures, even ones they ordered themselves.

- They have sometimes found results, but not the most recent ones.

- They have sometimes found the most recent results, but not earlier ones to make important comparisons.

- They have sometimes not been able to find reports from specialists, or have not looked.

- They have not been able to pull together a collation of the information relevant to a particular diagnosis.

These problems reflect human limitations which will not be eliminated by MHR. Data may be on the system but is not useful if it can’t be found and interpreted. Promotion of MHR as a “lifesaver” thus implies an ideal case that may not exist in practice.

Practitioner competence and time

Digital literacy among health professionals (and patients) is obviously variable, and the usefulness of MHR is limited proportionately.

The time available to practitioners, and their commitment to being thorough, also set limits to usefulness.

We all know, and largely understand, how difficult it can be for even the most committed general practitioners to cover the territory in the time allowed for a standard appointment if our health issues are complex. Specialist practitioners also vary in the time they spend with individual patients, regardless of how much they charge.

Additional human limitations that won’t be eliminated by MHR include:

- Doctors who don’t check the database even when it’s available. (I’ve been told of this

happening by someone who was part of the MHR trials).

happening by someone who was part of the MHR trials). - Doctors who check results for tests and procedures, but interpret them incorrectly.

- Doctors (or other data-handlers) who upload data to the wrong record.

- Doctors who fail to make connections between different tests and procedures which, taken together, may have greater diagnostic significance than each considered on its own.

The potential of MHR is thus limited by the reliability of the data uploaded to it, the navigability of the system, and human limitations of the data handlers. It provides, at best, an incomplete record with questionable value in an emergency.

As one submission to the Senate inquiry put it: “The agency behind My Health Record has grossly overstated the benefits to individuals…MHR is primarily a glorified Dropbox”.

Low care for patient care

“Data is seductive,” writes Kate Galloway. “Governments therefore have a tendency to try to use pools of it for as many purposes as possible” — including selling it for commercial purposes, making it available for research, and using it for political ends.

Patient care might rate a poor fourth on the list of government priorities.

Commercial purposes

Have you wondered, as I have, why a government committed primarily to business, and keen on cutting funds to public health services, would discover a driving concern for the everyday health of everyday citizens?

Have you wondered, as I have, why a government committed primarily to business, and keen on cutting funds to public health services, would discover a driving concern for the everyday health of everyday citizens?

The following quotes from Tim Kelsey are instructive.

Tim Kelsey is the chief executive of the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) which is responsible for MHR. He is a former entrepreneur, journalist, and government adviser, who came to Australia from the UK, where he was responsible for a parallel system that was abandoned in 2016. Patient data (including mental health information, diseases, and smoking habits) had been sold to insurers and drug companies. This, understandably, caused a public uproar.

Kelsey has spoken in public about the Australian government’s intention “to harness the power of the modern information revolution…to offer industry…a new platform for delivery of new services”.

His message to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia was that MHR is about “creating new industrial entrepreneurial opportunities for great apps developers.”

It was, incidentally, Kelsey’s team who secured legal authority in December 2017 to flip MHR from opt-in to opt-out. An opt-in system is preferable for optimising informed consent, but an opt-out system will harvest more of the population and yield correspondingly more data. It is thus better suited to the big data interests of big business and, given Kelsey’s background, this strikes me as a significant clue to the priorities.

Health insurance companies are keen to access MHR data. “We desperately need this data to make the world a better place,” says insurer, Mark Fitzgibbon, without specifying who it would be better for.

Health apps are already securing ‘consent’ through contracts that don’t make it immediately obvious that the app owner could sell your medical information to others.

Meanwhile, public concern about commercial use of MHR data is deflected by polispeak of safeguards. However, Phil Booth, coordinator of British privacy group Medconfidential, warns that “any safeguards that are promised will be routed around or ignored…On the basis of the evidence of what happened in England, they’re not worth the paper they’re written on.”

A company can, for example, escape being seen as ‘purely commercial’ (and hence ineligible for secondary access to data) if it has links to healthcare services. Such a clause might, for example, allow companies such as pathology or x-ray services to access MHR data. Information thus obtained might then (hypothetically) be sold to a purely commercial enterprise, such as a pharmaceutical company.

Health Engine, the medical appointment booking service, has already been exposed for selling data to personal injury lawyers, who then rang injured patients spruiking them to pursue litigation. The booking company claimed it had obtained consent – although you can’t use the service without agreeing to the terms of the “Collection Notice”!

It becomes clearer, perhaps, why our neoliberal government is keen to establish the MHR database. And, why there was so little public education about the system – no national television, radio or print media campaign, no letter to tell us about the scheme, its risks or even its benefits. No attempt, in other words, to meet the conditions for informed consent.

It becomes clearer, perhaps, why our neoliberal government is keen to establish the MHR database. And, why there was so little public education about the system – no national television, radio or print media campaign, no letter to tell us about the scheme, its risks or even its benefits. No attempt, in other words, to meet the conditions for informed consent.

Not even a fridge magnet!

As Julia Powles notes, “the difference of mission, between a tool for seamless information flow between patients and their healthcare providers, and a platform for industrial entrepreneurship, isn’t a mere detail – it is absolutely fundamental”.

We, who are deciding whether or not to opt out of MHR, need to be clear about what we would be getting into by allowing a record to be automatically created.

Research purposes

My initial reaction to the possibility of MHR data being used for research purposes was mild compared with the thought of it being exploited for profit.

There could, at least theoretically, be some real benefits for patients from health research on a large (deidentified) database.

The system is, for example, capable of storing genomic information, which can indicate genetic risk of developing cancer.

Five hundred million dollars has been committed by the federal government to Australian Genomics Health Alliance for research. The first project to be launched – The Australian Reproductive Carrier Screening Project (ARCSP) is a trial for detecting rare birth disorders.

Ten thousand would-be parents will get free testing to detect about 500 genes linked to severe disorders including spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), cystic fibrosis, and fragile X syndrome.

Many people might well support such research. But:

- Promises about deidentification of data for genomic (and other) research purposes are dubious given past precedent. In 2016, for example, the government released data on 9 million people. It included year of birth, gender, and medical information. IT researchers were able to demonstrate that the supposedly de-identified data could be re-identified and linked to the individuals concerned.

- The ADHA says patients can choose whether they want genomic test results uploaded, but its website does not mention this kind of data or how to exercise choice in excluding it.

- Australia still permits the use of genetic test results in life insurance underwriting. Genomic data, collected ostensibly for research purposes, would be highly valued by such companies. We would, I think, be naïve to accept that our data will be protected from such double-dipping.

Health research on population-wide MHR data may therefore have benefits, but also the risks of multipurposed sensitive data. In a climate of low confidence in government integrity and competence, such risks are significant.

Political purposes (in the ‘golden age of surveillance’)

There are plausible reasons for government enthusiasm for MHR. It should, for  example, reduce the number of duplicated tests, x-rays, and procedures. It should also reduce doctor-shopping. Estimated efficiencies are expected to save $300 million over three years.

example, reduce the number of duplicated tests, x-rays, and procedures. It should also reduce doctor-shopping. Estimated efficiencies are expected to save $300 million over three years.

There are, additionally, implicit reasons for a government with a penchant for surveillance to pursue MHR. Genomic data, in addition to its role in cancer research and detection of birth defects could, for example, provide a basis for ID – and hence for revival of an Australia Card.

The Aadhaar system in India illustrates the possible direction. Aadhaar is a 12-digit code, based on biometric data, which is unique to each individual. Indian citizens use the ID for everything from filing tax returns, to accessing pensions or welfare. An Aadhaar number is also recognised as valid proof of identity and residence.

An Aadhaar profile is built from an individual’s photos, finger prints, and iris scans. Genomic data could take such profiling to a further level of sophistication.

There has, to my knowledge, been no official reference to a potential segue from mining genomic data for research purposes to its function for surveillance purposes. I may, therefore, be starting at shadows. Politicians would no doubt claim so. If, however, my hypothesis is valid, government emphasis on the life-saving virtues of MHR would be disingenuous.

MHR, national ID, surveillance, and encryption

Extending the narrative, if there are dots to be joined between MHR, back-room agendas of a national ID, and mass surveillance, an additional key thread would be mining the data on our phones and other devices. Inroads have already been made through metadata retention laws, and new legislation is constantly in the pipeline.

Assistance and Access (encryption) Bill

As we make our decisions about whether or not to opt-out of MHR, the Assistance and Access Bill is before parliament. This bill would allow intelligence and law enforcement agencies greater access to encrypted data. It would give them power to ask or force any provider of communications services and devices in Australia to help them do so.

Penalties for being uncooperative include fines of up to $10 million for companies that refuse to facilitate access to encrypted data, and 10 years’ jail for individuals who refuse to provide their passwords.

The communications industry, unsurprisingly, has raised objections and called for independent judicial oversight.

Industry bodies have formed an Alliance to oppose the bill, joining forces with groups including Digital Rights Watch, the Human Rights Law Centre, Amnesty International, and Access Now.

“We should all be worried,” says Lizzie O’Shea, spokesperson for the Alliance and board member of Digital Rights Watch. “This legislation doesn’t only target criminals, it puts every Australian at risk…Creating tools to weaken encrypted systems for one purpose weakens it for all purposes.”

From national security to national revenue

An additional concern is that the remit of the encryption bill extends beyond national security to protection of national revenue. This raises disturbing possibilities.

Surveillance of Centrelink recipients is one implicit possibility. Surveillance of protestors, who might, for example, cost revenue on mining sites, is another. NDIS investigations and workers compensation processes are additional risk areas.

Kate Galloway notes the inevitable impact of mass data collection programs such as MHR on the relationship between citizen and state. In this case, the citizen needs to weigh promises of improved health care (for some people some of the time) against increased government power, and threats to civil rights and privacy (for all).

Patient care

How, then, do in-principle objections stack up against potential individual gains, particularly for those with complex health problems?

I’m not going to attempt to answer this question in any general way. I’m having enough trouble with my own decision. My hope, though, is that people will seriously consider the pros and cons of opting out, and not simply go with the default, which would mean having a record automatically created.

You can opt out until 15 November, 2018, and no record will be established. It will also be possible to cancel an established record after that date, and the health minister has promised that this can be done completely and permanently at any time.

Robert Merkel, software engineer, does however raise questions about permanent deletion of records. If a user requests deletion, he writes, removing their record from the active database will be relatively straightforward, but removing them from the backups is not.

It is unclear, according to Merkel, whether law enforcement bodies, or anyone else, could potentially access a deleted record if they were granted access to archival backups by the system operator, ADHA.

It seems wiser to make a preemptive call.

Multiple agendas compromise privacy

A central database, such as MHR, is ideal for data-sharing and thus has clear advantages for governments, businesses, and research organisations. (Also cyber thieves.) However, if patient care was the main priority, a distributed system, where each person retained control over their own data would provide vastly improved potential for privacy and security.

Privacy for individuals may not be the first priority of governments. The official position of the Five Eyes intelligence partners (Australia, Canada, NZ, Britain, and US governments) is that “privacy is not absolute”.

Citizen backlash over privacy of MHR data particularly targeted police access. The outcry was sufficient for government to make concessions. The health minister issued a statement that the legislation would be amended so that “no record can be released to police or government agencies, for any purpose, without a court order”.

Former Australian Medical Association (AMA) president, Kerryn Phelps, has described the concessions as “woefully inadequate” and called for a full parliamentary inquiry.

“If [MHR] truly is about the wellbeing of patients,” she said, “there is absolutely no need for third party access to be in the legislation.”

Phelps expressed particular concern about Section 98 of the MHR Act, which gives ADHA the power, as the system operator, to delegate any function to any other person with consent of the minister. “This could include the disclosure of your health information,” she said.

Government has a bad record of misusing its power, Paddy Manning notes, citing several examples since the Liberal National Party took office in 2013. “There is a real fear that government might decide to dig into the private health records of individuals for its own reasons.”

Those reasons, as already argued, could have long tentacles into mass surveillance.

System (in)security

The risks to privacy from third-party access to MHR data are compounded by problems of system security.

MHR is part of a long history of poorly executed big data projects by the Australian government, write Lizzie O’Shea and Justin Warren. The online census and the data matching of tax and Centrelink records both ended in scandal, and yet government persists with yet more projects.

“There is a neoliberal ideal in government that we can make everything more efficient with technology,” says Dr Monique Mann of the Australian Privacy Foundation. “But these big data omnishambles show the opposite is true.” There are inherent tensions in designing a system that is secure and private but also designed to share information with multiple parties.

According to cyber security expert Greg Austin, “the government is showing no interest in innovative approaches to privacy protection. It is showing a high degree of incompetence in protecting its own systems. It manifests a low degree of cyber security across the board.”

Given the appeal of health data to hackers and identity thieves, this is cause for serious concern.

Groups at risk from breaches of privacy

Privacy breaches are particularly high risk for employees, adolescents, those in family dispute and domestic violence situations, and those with mental health issues.

A substantial proportion of the population, in fact!

Employees

Unions have urged members to opt out of MHR because employer doctors (used, for example, for pre-employment health checks) could access, and then pass on to prospective employers, a worker’s entire medical history. Workers compensation claimants have also been warned to be wary about privacy.

The ADHA attempts to soothe these fears by saying it “does not consider an employment check is healthcare and therefore use of the My Health Record would not be permitted.”

What is permitted, however, and what is technically possible, are two distinct propositions, as Anna Johnston, former privacy commissioner, notes.

Legal experts say the unions have a case because the laws governing access are spread across several pieces of legislation and the rules are unclear.

“There are so many holes in the My Records Act, so much uncertainty in its flaccid drafting and so little regulation that there is a significant likelihood of unintended consequences,” says barrister, Peter A Clarke, who has a particular interest in privacy.

As a basic precaution, advises lawyer Tom Ballantyne, workers should adjust their privacy settings to protect themselves as much as possible by restricting access to their data.

Adolescents

Young Australians are legally entitled to confidential health care, but default settings on MHR do not adequately protect their privacy, warn Melissa Kang and Lena Sanci.

Parents can access parts of their children’s MHR until they turn 18, including clinical notes, non-PBS medications, and specialists’ letters. Medicare-rebated services, including GP consultations, and PBS-subsidised scripts will not, however, be visible to parents once adolescents turn 14, even if they are still on the family Medicare card.

Adolescents can opt-out of MHR if they have turned 14, or parents can opt-out younger children. Those who do not opt-out can protect their privacy to some extent by adjusting their privacy settings. They can also ask health professionals not to upload sensitive data, although test results and x-rays may be uploaded before reaching the GP. To prevent this, the doctor requesting the procedure would need to instruct the service provider not to upload the data.

Health providers need to remember to ask young people whether or not they want specific data uploaded. Young people need to have the confidence to instruct practitioners and to know they are entitled to do so.

If either party doesn’t initiate an opt-out, some data will be automatically uploaded.

Sounds precarious.

Dr Robert Walker, who works with teenagers in a school, is worried that trust will be undermined by MHR information being accessible to parents. He says his team has managed to significantly reduce the teenage pregnancy rate, stop the spread of sexually transmitted infections, and help many students with mental health issues. But that work depends on confidentiality between doctor and patient, and current MHR arrangements threaten that.

Those involved in family disputes

A specific problem of parental access can occur in family dispute and domestic violence situations. A loophole in the MHR system allows a parent who does not have primary custody to create a record on their child’s behalf, without the consent or knowledge of their former partner.

Having created such a record, it might then be possible to discover the general whereabouts of children and their custodial parent through information on the MHR (such as location of GP clinics or pharmacies attended, for example). This could be dangerous in violent circumstances.

To prevent such a situation, either parent can request the ADHA to suspend their child’s personal identification number (which is linked to their Medicare number and thus identical if both parents have created records).

The ADHA then assesses requests by the respective parents to access MHR on their child’s behalf.

If both parents are approved, either parent could access a child’s record without the other’s consent.

If one parent is denied access they could contest the decision in the Family Court. And, “unless a primary caregiver has a Family Court order granting them sole responsibility in regard to medical treatment [a rare occurrence],” says Angela Lynch, chief executive of a Women’s Legal Service, “a refusal of access [by the ADHA] would be unlikely to withstand a legal challenge.”

Thus the ADHA ‘safeguard’ is another precarious arrangement that you would be understandably reluctant to trust if your safety, and that of your children, was at stake.

Those with mental health issues

Australians with mental health diagnoses have been urged to consider opting out of MHR on the grounds that they could experience discrimination if their digital medical material was stolen, leaked, made accessible to employers, or handed over for commercial or research purposes.

Australians with mental health diagnoses have been urged to consider opting out of MHR on the grounds that they could experience discrimination if their digital medical material was stolen, leaked, made accessible to employers, or handed over for commercial or research purposes.

Three mental health bodies – Consumers of Mental Health WA, the Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council, and the NSW peak organisation, Being, have said they consider the risk of privacy breaches is too high for comfort where mental health information is concerned.

Even with high confidence in the legal framework and system security, there would be pause for thought. Under existing circumstances, the basis for caution is strong.

I’ve had discussions with people who argue there should be no reason to fear discrimination on mental health grounds. Residual stigma should be fought at a broader social level, they say. If discrimination does occur it should be challenged, legally if necessary.

I agree, in principle, but think discrimination frequently operates covertly. An employer, for example, is unlikely to name mental health, or disability, as a reason for rejection of a job applicant, any more than they would name age or gender as deciding factors.

We also have a long way to go in eliminating stigma, and weighing up the pros and cons of MHR is an individual prerogative. Mental health issues add an additional layer of complexity to an already challenging decision.

Create your own health record

Dr Adrian Pokorny expresses (limited) support for the concept of MHR, but says he is opting out himself. He argues for an opt-in system and recommends that those who opt-out carry their own record of major medical problems, current medications (name, dose, form such as pill, frequency, time taken, purpose, and prescriber), allergies, doctors, Medicare and health insurance information, emergency contact details, and blood type (if known).

Don’t limit your list to prescription medications, Dennis Thompson recommends. Include over-the-counter products as well as herbal supplements.

As a comment on that advice, I recently learnt from pharmacists that supplements I was taking for arthritis and general immunity (Omega-3 and Olive Leaf extract) are not recommended when taking blood-thinning medication, which I am.

If you decide to opt out

The opt-out period ends on November 15, 2018. Anyone who has not opted out by that date will have a MHR automatically created. You can opt out here.

As of 12 September 2018, a Senate inquiry was told:

- 900,000 people had opted-out online since the system opened on 16 July. Paper forms had not yet been processed.

- 20,957 had set codes to restrict access either completely or partly.

- 136,644 had activated the alert to be notified when a new practitioner accesses their record.

Access controls are not the default, according to the ADHA, because that “could impact the system’s effectiveness” – for creating a mass data base for government, commercial, and research purposes, presumably. “Effectiveness” in this context can’t refer to patient care, because access controls can be overridden in an emergency.

You can opt out here.

Personal versus political impasse

Returning to the decision about opting out, I realise I have opposing positions on personal and political levels.

On a personal basis, staying in makes some sense. There may be some benefits given my health issues, there are no obvious personal disadvantages, and my family would prefer me to be ‘in’.

I recently spent a night in emergency, and the doctors would have liked access to previous tests, x-rays, and practitioners’ details. I did have all that information at home, mainly on paper, but couldn’t access it from hospital. There are ways around this, such as having the information digitised and portable, but an MHR would also have served the purpose.

On a political level, on the other hand, I would opt out.

- I do not believe our current neoliberal government has the best interests of the majority of citizens at heart. I therefore do not anticipate a system that optimises data quality for patient care.

- Rather, the priorities appear to be those of commercial, research, and political interests. I am wary of the pursuit of surveillance under the guise of ‘national security’, and have niggling questions about the potential mining of health data to enable such surveillance.

- Government’s track record is not encouraging in terms of implementing best practice systems and state-of-the-art security to protect individual rights and privacy. Assurances about safeguards are unconvincing, and the will to regulate illegal data mining is lacking.

- If I was in a group at high risk from privacy breaches I would be dubious about supposed protections.

On balance, I would opt out on principle, create my own digital record, and hope the MHR system collapses under the weight of people voting with their feet. It might then be possible to take the idea back to the drawing board with patient care at the centre of development.

That would, however, involve disregarding the wishes of my family, and I don’t want to do that.

What to do? Time is running out. What are you doing? Opting-out? Sticking with the default? What issues are important to you in making your decision about My Health Record?

Your comments are welcome…Joan Beckwith

Scroll down for COMMENTS

First-time comments have to be moderated

I try to complete that process, and respond, within 24 hours

Do check back

Social justice is for everyone (previously 2020socialjustice) is also on Facebook (click here)

Joan Beckwith on Twitter (click here)

…………………………………………….

NOTE: If you like this post, you might also be interested in browsing the site, perhaps starting with the Favorites category, which brings together a selection of posts from across other main categories.

happening by someone who was part of the MHR

happening by someone who was part of the MHR

It’s a really very useful and also very informative blog for me. Thanks a lot for sharing the blog and also the useful information’s. Appreciate this article to help us read between the lines to get to the truth.

Thanks for your feedback, Samuel. It’s good to hear the information is useful.

Interesting article in The Saturday Paper (so may be behind paywall if no subscription) written by a medical practitioner, concluding that MHR is “not fit for purpose” and noting it cost $2 billion to establish, and $500 million a year to run for likely savings of less than that. https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/opinion/topic/2019/02/02/opting-out-my-health-record/15490260007388

Opt-out period EXTENDED TO 31 JANUARY 2019 https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2018-11-14/my-health-record-opt-out-deadline-amendments-privacy-security/10481806

Article that came out at the same time as the extended deadline was announced on the pros and cons of opting out https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/national/2018/11/14/my-health-record-for-against/?utm_source=Adestra&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Morning%20News%20-%2020181115

Amazing. In news reported on 9 November 2018 (6 days before the cut-off date for opting out) the director of privacy for MHR has quit, “amid claims the organisation and Health Minister Greg Hunt’s office have not been taking the concerns of internal privacy experts seriously enough” (follow the link).

https://www.smh.com.au/technology/my-health-record-s-privacy-chief-quits-amid-claims-agency-not-listening-20181107-p50elu.html?fbclid=IwAR1GycpymP9UtwlNSL3ljmg7GdIiPdOOWUGCm4Vgi_tKdO6XfcszFRcvc_s

Additional article post-publication of my post about proposed changes to legislation to increase ‘safeguards’:

https://www.sbs.com.au/news/greg-hunt-moves-to-toughen-penalties-for-my-health-record-misuse?cx_cid=edm:newsam:2019

Thanks Joan for comprehensive thoughtful review. I have been in avoidance re making a decision since my health became more complicated and uncertain requiring multiple care providers. That said I have decided to opt out on three grounds

Political

Lack of trust in the govt ability to ensure privacy and integrity based on previous multiple data breaches

Cannot see that the MHR data collection system is of sufficient integrity to be useful.

Those three grounds pretty much sum it up for me too, Pamela. My potentially additional grounds about commercial exploitation of the database, and a segue into revival of the Australia Card (and thence to mass surveillance) probably fall under the umbrella of lack of trust in government. Of course we are being assured of safeguards against commercial use, and there has, to my knowledge, not even been talk of my hypothetical segue (and if there was my concerns would no doubt be dismissed as paranoia). But, really, we are being asked to take a lot on trust, which is a big ask, particularly of this government. Further, even if legal safeguards were as comprehensive as possible, what is legal and what can (and might) be done are two separate questions, as pointed out by one of the sources cited in the post.

Your third point, about the questionable usefulness of the database for individual patient care (as distinct from big-data agendas) has been a clincher for other people I know. If it’s not fit for that purpose, why would anyone sign up for it, you might ask.

Recommendations from the Senate inquiry into MHR with comments from Australian Privacy Foundation https://privacy.org.au/campaigns/myhr/

The full report: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/MyHealthRecordsystem/Final_report

I have yet to get any answer, much less a satisfactory one, to the question “even though I have opted out (on day one), what guarantee do I have that no MHR will be created for me?”

It’s a good question, Kevin, and one that has previously also been raised on an earlier Facebook promo of this post. I think it’s something that is only going to be check-able after the fact. Hopefully you, and many others, will be doing that checking and there will be an almighty uproar if records are created for people who have opted out.

My own situation is that I had a pre-existing record from the system that predated this one. I was able to ‘cancel’ that record, but not opt out as such, or delete the existing record. When I said I wanted to delete it, I was told that the option of deleting a record has not yet been legislated. However, I was told that no MHR would be created for me because I have cancelled the existing record. I will certainly be following up, both the MHR aspect, and the deletion one.

This article (link follows), by a medical practitioner, is not one that I had when I wrote my post (above). It’s worth reading, I think, because it reinforces the limits of usefulness of MHR for patient care. Test results etc. will, he reports, be uploaded as they are done as individual scanned copies of PDF files. There will be no collation of test results over time.

Interestingly, this doctor also reports that on his own record he found that he had supposedly been prescribed medications for breast cancer. Twice.

This kind of mistake can, of course happen now, but it remains a caution in relation to the spin about ‘saving lives’ with MHR.

To quote Dr Freeman:

“The clinically useful data I hoped to see, like atomic pathology results that would show how a patient’s blood results have been tracking over time; sadly, that’s not there and apparently it’s not on the roadmap either. The only way to find a result is to painstakingly sift through what amounts to scanned PDF copies of all the pathology results a patient has ever had.

All up it seems like a pretty large loss of privacy for a negligible gain in utility (Dr James Freeman, 2018).”

https://www.michaelwest.com.au/my-health-record-the-doctors-tale/?fbclid=IwAR3OYWkXJnlIizcSbjZxqdOlx-5tmrRUEA37PfFAfFNVq-L_ah5byqUR1Xk

Very informative article with a lot to consider, including the underlying reasons that governments may want to do this sort of thing!!

I’ve already opted out.

It seems to me that all big data systems can be hacked relatively easily, and/or will be hacked sooner or later.

I’ve been ‘lucky’ with health over the years, and ‘pretty much’ only went to a doctor when I wanted a day off and had used up my few days ‘without a certificate’. Used almost none of sick leave over the years – would have been very nice if I’d received a payout on what was owing when I finally retired!!

Thanks for your comment, Richard. I agree there is a lot to think about, and various reasons for opting out. Fewer for staying in, I think, if you unpack the “lifesaving” spin.

Interesting thought, the idea of being paid out for un-used sick leave (which is an entitlement after all!) Not likely to happen in the current climate, but it could make retirement more comfortable for a lot of people, I imagine. On the other hand, with the increasing trend to casual and contract employment, a diminishing number of people have any sick leave entitlements even while working.

I hope you stay well, and have little need for health services, with or without an e-record!