Why can’t we learn some Finnish lessons? The Minister explains

May 7th, 2016 | Published in Education

“Why can’t we be as good as the Finns?” asks Ned Manning, teacher of forty years, in relation to the Australian education system.

“I’ll tell you why,” he answers his own question:

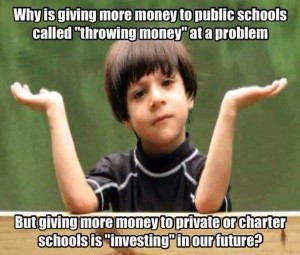

• The Finns don’t argue about who should fund their schools.

• They don’t waste ink on public versus private arguments.

• They don’t bag their teachers.

• They have manageable class sizes.

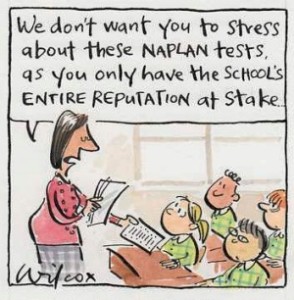

• They have virtually discarded standardised testing.

Better education, he concludes, “has nothing to do with better teachers. It’s got everything to do with protecting our children from politicians.” Current educators are competent, in other words, and education needs to be handed back to them!

Manning’s enthusiasm for the Finnish system is supported by Michael Moore’s documentary, “Where to Invade Next“, and his concern over standardised tests is shared in the UK.

I found myself nodding as I read Manning’s article, and remembering my own study of standardised testing as part of my PhD, which left me keenly aware of the gulf between the richness of the concepts we would like to measure (in this case “learning”) and our capacity to capture them in standardised tests.

Let’s ask the Minister for Education

Manning’s article generated substantial discussion on my Facebook page and someone suggested asking the current Minister for Education, Simon Birmingham, for comment.

So, I sent an email, including the parts of the article shown above. Several days later I received a Departmental Response. Not bad, I thought, considering I’m still waiting to hear back from Tony Abbott about letters I wrote to him in his early days as Prime Minister in 2013, nearly two and a half years ago!

The Minister’s office responds (22 April 2016)

Dear Dr Beckwith

Thank you for your email of 16 April 2016 to Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham, Minister for Education and Training, concerning comparisons between Australia’s and Finland’s education systems raised in Ned Manning’s article in the Sydney Morning Herald on 12 April 2016. I have been asked to reply on the Minister’s behalf.

As you would appreciate, no two countries share the same educational or cultural contexts. That said, it is always possible to learn from the experiences of others and Australia is open to learning from what works in other high performing education systems, including Finland. It is interesting to note that the Australian and Finnish education systems share some key characteristics, such as uniform basic education for whole age groups, highly competent teachers, school autonomy and a commitment to providing educational opportunities to all students.

The Australian Government is committed to lifting the quality and status of the teaching profession in Australia and believes that action is needed from the very start — at the point of admission to teacher training courses. To address this, the Government is improving admission standards for initial teacher education programmes by encouraging greater attention to the qualities that make good teachers, such as good communication skills and motivation to work with young people, in combination with academic skills. The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) has been tasked with developing guidelines for teacher selection that set clear expectations of universities in making sure that those going into teaching have the right mix of academic and personal qualities that give them the best chance of becoming effective teachers. Further, from 2016 all teacher education students will be required to pass a national literacy and numeracy test before they graduate.

In both Finland and Australia, class sizes are smaller than on average across countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). I am aware that class sizes can affect learning in various ways and teachers may have to adopt different pedagogical styles. According to the the OECD, however„ the relationship between smaller classes and better performance is relatively weak and likely to be culture−specific. For example, many of the East Asian nations that are top performers in international assessments have comparatively large class sizes.

In his article, Mr Manning raises the issue of standardised testing, noting that ‘the Finns have virtually discarded standardised testing, and…we have become more and more reliant on NAPLAN results for meaningless and costly data that enables us to identify the best schools.’ I would point out that NAPLAN is not focussed only on raising the profile of high performing schools and that the way the results are represented on the My School website is explicitly designed to discourage attempts to construct so called ‘league tables’.

One of the purposes of NAPLAN is for educational authorities and schools to determine whether or not students have the literacy and numeracy skills that provide the critical foundations for their learning. At the school level, schools benefit by gaining detailed information on how their students are performing, and can identify areas where more instruction may be required. The outcomes of the NAPLAN assessment are also used to inform future policy development, curriculum planning, intervention programs, and priority areas for resourcing, so that funds can be used where they are most needed.

The findings from international assessments provide information on the progress of Australian school students relative to students from other countries and assist the Government to identify strengths and weaknesses in schooling policies and practices. Results from the 2012 cycle of the Programme for International Student Assessment show that although Australian children continue to perform well compared with the OECD average, our results in reading and mathematical literacy have declined in absolute terms and relative to other countries. The results also show that our top students are not performing as well as their peers in other countries and that we have more low performing students than previously.

This shows that, despite significant increases in funding, we are not seeing the sorts of improvements the Government is seeking. The lack of improvement in student outcomes over recent years is concerning because educational outcomes provide the strongest basis for Australia’s continued economic prosperity and productivity, as well as the strength of its civil society. Higher levels of education attainment are linked to higher levels of employment, productivity and wages.

This shows that, despite significant increases in funding, we are not seeing the sorts of improvements the Government is seeking. The lack of improvement in student outcomes over recent years is concerning because educational outcomes provide the strongest basis for Australia’s continued economic prosperity and productivity, as well as the strength of its civil society. Higher levels of education attainment are linked to higher levels of employment, productivity and wages.

That is why the Government is working with states and territories and the non−government sector to improve outcomes in Australian schools. The Students First package of reforms will improve outcomes by focusing on four key pillars of education that evidence shows can make a real difference: improving teacher quality, increasing school autonomy, engaging parents in education, and strengthening the curriculum.

Unfortunately, there is no one formula that can be imported from one country and be guaranteed to succeed in another. That is why it is important that schooling policy in Australia continues to explore best practice from around the world but that where such practices are adopted they are adjusted to address Australia’s unique education culture and circumstances.

Thank you for bringing this matter to the Government’s attention.

Yours sincerely

Rhyan Bloor, Branch Manager, Assessment and Early Learning Branch

Australian Government Department of Education and Training

Not a form letter, but…

This is not the kind of form response I have come to expect from the current regime (successive Ministers for Immigration, for example), and I should, and do, appreciate the effort put into it. Nonetheless, it leaves me dissatisfied on a number of grounds:

- It doesn’t respond to the push by federal government to abandon funding of public schools while continuing to fund ‘independent’ schools (Manning’s first two points; also discussed more fully in a related post).

- It subtly reinforces the “bagging” of teachers (despite reference to “highly competent teachers” as a characteristic shared with the Finns) by promising to “improve admission standards” and require trainees to pass a “national literacy and numeracy test before they graduate”. The irony of this suggestion in the face of Manning’s criticism of standardised testing for students is not noted.

- It sidesteps the issue of class sizes by referring to East Asian countries with comparatively large class sizes that are “top performers” – on international standardised tests!

- It responds, in other words, within the managerialist frame of reference that is the basis of concern in the first place. There’s nothing actually ‘wrong’ with the answer, but it perpetuates the conflation of education with test results and thus glances off Manning’s critique.

How is it possible to have a meaningful discussion about education (or anything else) when those with the decision-making power constrain the conversation to their existing narrative?…Joan Beckwith.

******************************

Scroll down for comments

First-time comments have to be moderated. I try to complete that process within 24 hours. Do check back. I greatly value involvement, always read comments, and respond to most. After your first comment, subsequent ones should appear automatically.

Social justice is for everyone (previously 2020socialjustice) is also on Facebook (click here)

And Twitter (click here)

Related article on the emerging phenomenon of segregation in state schools along racial and economic lines, enabled by NAPLAN data on the MySchool website

http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/white-flight-why-are-our-state-schools-segregating-20160503-gokutm.html